Reflections on History from a (Temporary) Missourian

On October 1, 2020, I landed at Kansas City International Airport with a single suitcase of clothes. At that point, I never would have imagined how I would become enamored with the Kansas City art community over the following two years. The idea of “looking out” for one another could be a Midwest thing. I certainly had not experienced this level of care in Los Angeles, New York, the San Francisco Bay Area, the rural borough of Lewisburg, PA, or the suburban city of Troy, NY. This innate sense of community, and the ways in which these artists genuinely care for each other’s practice and well-being, is how I will always think of Kansas City.

I would consider myself a temporary Missourian. I knew I would live in Missouri for a couple years, as my role is a fixed two-year period. The allure of Kansas City and its generous artistic community necessitate more time for me to understand them fully. I have dedicated time to walking along the banks of the Missouri River and pouring over books in the Missouri Valley Room of the Kansas City Public Library; my impulse to learn about the history of a place comes from an art historical frame of mind. In visual and material culture, artworks are signifiers of a particular time, place, and political context. Knowing more about a city—its geographies, cultural values, and civic issues—provides insight into these artists and the work they are making today.

The place of Kansas City has a complicated history, like most American cities. In the historical publication, Racism in Kansas City: A Short History, G.S. Griffin guides readers through harrowing accounts of racial inequities in the Kansas City metropolitan area from the 1800s to the present. The awareness of Kansas City’s histories enhances our collective understanding of institutionalized, structural forms of racism, from housing rights and wealth inequities to the long-term impacts of a segregated public educational system. Early in the book, Griffin recounts the story of a black explorer and enslaved person named York, whose narrative has been uncovered by historians and finally acknowledged two hundred years later. Alongside Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, York embarked on the exploration across the United States: he was the first African American person to travel from coast to coast. In 1804, their expedition brought them to the mouth of the Kaw (Kansas) River, the location where Kansas City would be established one day. This geographical point is a significant boundary between Kansas City, Missouri and Kansas City, Kansas. The notions of invisible boundaries and crossing points, namely Kaw Point, inspired the imagery in this text by Hope-Lian Vinson.

Hope-Lian Vinson

Stepping back to state histories, Missouri officially entered the Union in 1821 as the 24th state of the United States. In honor of its founding, the State Historical Society of Missouri launched a statewide commemoration of the Missouri Bicentennial in 2021. As part of this initiative, I collaborated on the Kemper Museum’s exhibition Contemporary Art and the Missouri Bicentennial, drawing upon artworks including Wilbur Niewald’s Current River II (1965) and Siah Armajani’s Kansas City No. 1 (2000). While the official Missouri Bicentennial language refers to the “State of Missouri’s rich and complex history,” it neglects to name the indigenous stewards of the land we call Kansas City, and omits that Missouri was a slave state when it entered the Union. The selective description of Missouri’s history prompts questions as to who is shaping these narratives and who is articulating the “official” histories. Just like the historical account of the black explorer York, some compelling Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) stories have been overlooked by historians to build a singular “authoritative” version of history.

As an emerging curator of color, I often contemplate this critical reading of history, and advocate for BIPOC perspectives in mainstream cultural spaces. Starting with my first exhibition in 2013, I focused on working with BIPOC artists, and this arc of my curatorial practice is still urgent in the predominantly white cultural spaces of Kansas City. In the recent U.S. Census data of 2020, the racial demographics of Kansas City estimate 60.3% white, 27.7% black, and 10.6% Hispanic or Latino populations. I am a part of the 4.8% of Two or More Races demographic, a narrow fragment of the total urban population. The racial compositions of the city provide some larger social frameworks to examine cultural production. The artists, performers, musicians, writers, and other creative producers in the city might find spaces that support and elevate BIPOC voices, or create their own communities and collectives. For example, the artist-run spaces Curiouser & Curiouser and The Ekru Project have BIPOC organizers, in addition to the collective Strange Fruit Femmes and the long-standing African American Artist Collective (AAAC). An Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) artist collective formed in early 2021, following the anti-Asian shooting in Atlanta that took the lives of eight people. The collective’s virtual meetings generated a shared space of solace in the aftermath of the hate crime. Seeing the faces of other Asian American artists and organizers gave me some reassurance, and we were unpacking similar issues together. Being an Asian-American in the Midwest feels isolating at times, and the AAPI collective created a net of support and solidarity.

Hope-Lian Vinson

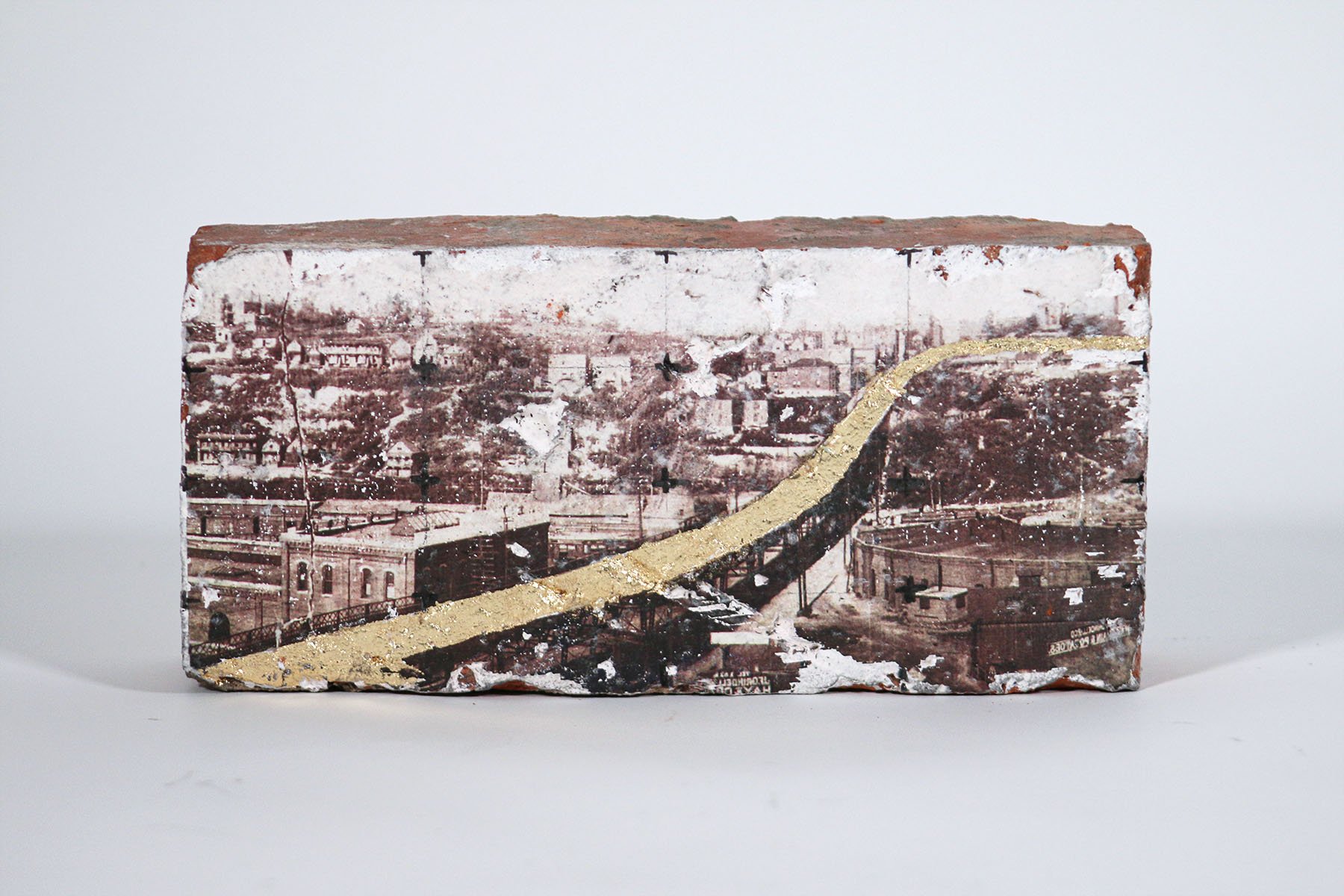

On the day of the Atlanta spa shooting, one of the artists in the AAPI collective named Hope reached out to check in. I will always remember that simple gesture of care, and this also speaks to the earlier mention of “looking out” for one another. The artist Hope-Lian Vinson makes works that are deeply rooted in ideas of place, material histories, and the archaeological layering of time. Their work was recently featured in the first iteration of Site One (read more in an upcoming Atlas text by Kevin Umaña) as well as Sapien Gallery. Scouring the archival collections of Mid-Continent Public Library, the artist collected historical images of the Missouri River, and the confluence of the Missouri River and Kansas River at Kaw Point; bridges and flood lines were incorporated into the visual language of the works to reference architectural and topographical moments.

Vinson’s artworks, interspersed with this text, function as an amalgamation of past and present. The artist layers the archival imagery onto a brick surface as a photographic transfer. Vinson sourced found bricks from construction sites in Kansas City’s Crossroads neighborhood, a physical signifier of the rapid gentrification in the Crossroads and ubiquitous construction sites throughout the city. The brick, acting as a contemporary marker of time, also alludes to the brick-laying histories of early Kansas City with its red brick-paved roads.

For me, it is imperative to understand the past to feel grounded in the present, and to imagine a radical future. Reflecting on the aforementioned book Racism in Kansas City: A Short History, the landscape of Kansas City holds the racial trauma of generations, such as sites of lynchings and hate crimes. The awareness of these histories precipitates a personal stake in political action and a push toward social change on a larger scale. When I disembarked from the plane in October 2020, I had barely any knowledge of Missouri’s histories. This quest to unravel different narratives through research and writing has generated a deeper understanding of present-day Kansas City. In a similar way, Hope-Lian Vinson’s work embraces a research-based practice, as do several writers for the MDW Atlas for Missouri. The selected contributors for the Kansas City texts are brilliant change-makers, poets, and artists: Chad Onianwa, Kevin Umaña, and Rachel Atakpa. These voices speak eloquently regarding who we are, what we value, and what we hope for Kansas City in its future.

Hope-Lian Vinson

Kimi Kitada is the July Editor for Missouri, selected by Charlotte Street Foundation.