Markings of Remembrance

The First Time

Bryn Jackson (BJ): We recruited an intimate group of 8-10 people in the Filipino American community through a call-out flyer sent out to several networks and social media channels. The recently established Philippine Cultural Community Center connected us more with Filipino and Filipino American (FilAm) businesses, vendors, and community spaces in the area, and hosted our first meeting as a group. It was January, and the cold was brutal. I remember being nervous that the weather would keep people at home, but most of the cohort attended. We started with simple ice breakers, but when it came time to introduce ourselves in depth and discuss why we were all interested in coming together to talk about ancestral Filipino body art traditions, the conversation quickly became candid. Our first real question was “Why are you here?” and almost immediately, we started sharing our experiences.

What Surrounds Us

April Knauber (AK): I was born in Cincinnati and moved to Indianapolis nine years ago for my education at Herron School of Art + Design. In 2019, I received my BFA in sculpture with a minor in art history. Since graduating, I have been a practicing artist working primarily in sculpture and in video art. Using readymades, concrete, and assembling and disassembling objects into artworks ties closely into my Filipino-American heritage of “using what you have.” Concrete is widely used in my practice, not just for its accessibility and reliability to the working class, but for the physical and conceptual heaviness it adds to a piece. My work revolves around immigration, classism, and colonialism, as these are topics that cannot exist without the other. I have shown in galleries and museums around the country.

When I started becoming involved as a visual artist in the Indianapolis arts scene and community, I noticed there was little representation of Filipinos and the FilAm community. I found this interesting, because Filipinos are such creative people in multiple disciplines (music, dance, theater, etc.) My mother immigrated to the U.S. in 1993, so I grew up surrounded by Filipinos and FilAms my whole life.

BJ: I grew up in Indianapolis and moved to New York in 2006 to study Film & Television Production at New York University. I moved to Chicago in 2013 and received my MFA in Art & Technology Studies from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2015. My work centers nature and the built environment as a means of unpacking and connecting disparate narratives, personal experiences, and material culture. Through sculptural, digital, photographic, and time-based media production, I grapple with themes of ecological inequity and institutional accountability, and I insist upon a more ethical and equitable stewardship of art, artists, and our communities, ecosystems, and histories.

Through researching my own history, I learned that my family moved to the states around 1960. This was a period when parts of the Midwest were seeing an influx of Filipino people. The Philippines were granted sovereignty in the 1940s, and labor was (and still is) one of the country’s leading exports. So, most of my own experience of Filipino culture was strongly rooted in my nuclear family, which had made its way to Indiana in the 70s and 80s.

When I was in my teens, my mother found community in organizations like the Barangay Club, the Philippine Nurses Association, and the Asian American Alliance, and from this network emerged groups dedicated to strengthening ties between members of the diaspora and sharing our arts and culture through events like the Indy International Festival.

But in my adult life, it increasingly feels like I don’t encounter other Filipinos in dedicated art spaces unless I seek out spaces that are designed by us and for us. This has been particularly true in the professional spaces I’ve navigated, which is why I’m grateful to be partnered with April and the Philippine Cultural Community Center to create space to cultivate collective memory.

Discovery and Practice: Ancestral Tattoo Traditions

AK: I knew about traditional Filipino tattooing but never really looked into it that much. That being said, there is a revival of indigenous tattooing happening across all cultures, and in terms of Filipino tattooing, you can see it happening back in the motherland and in pockets throughout the USA. Our cohort, Bryn, and myself got to really dive deep into the research, and I feel like that is because we were on this ride together. While a lot of our research is learning the techniques, history, and meanings of tattoos, a lot of it dealt with heavy topics as well that we had to face. And being able to have the support system we had with this group allowed us to face it together. There were definitely multiple meetings where tears were shed.

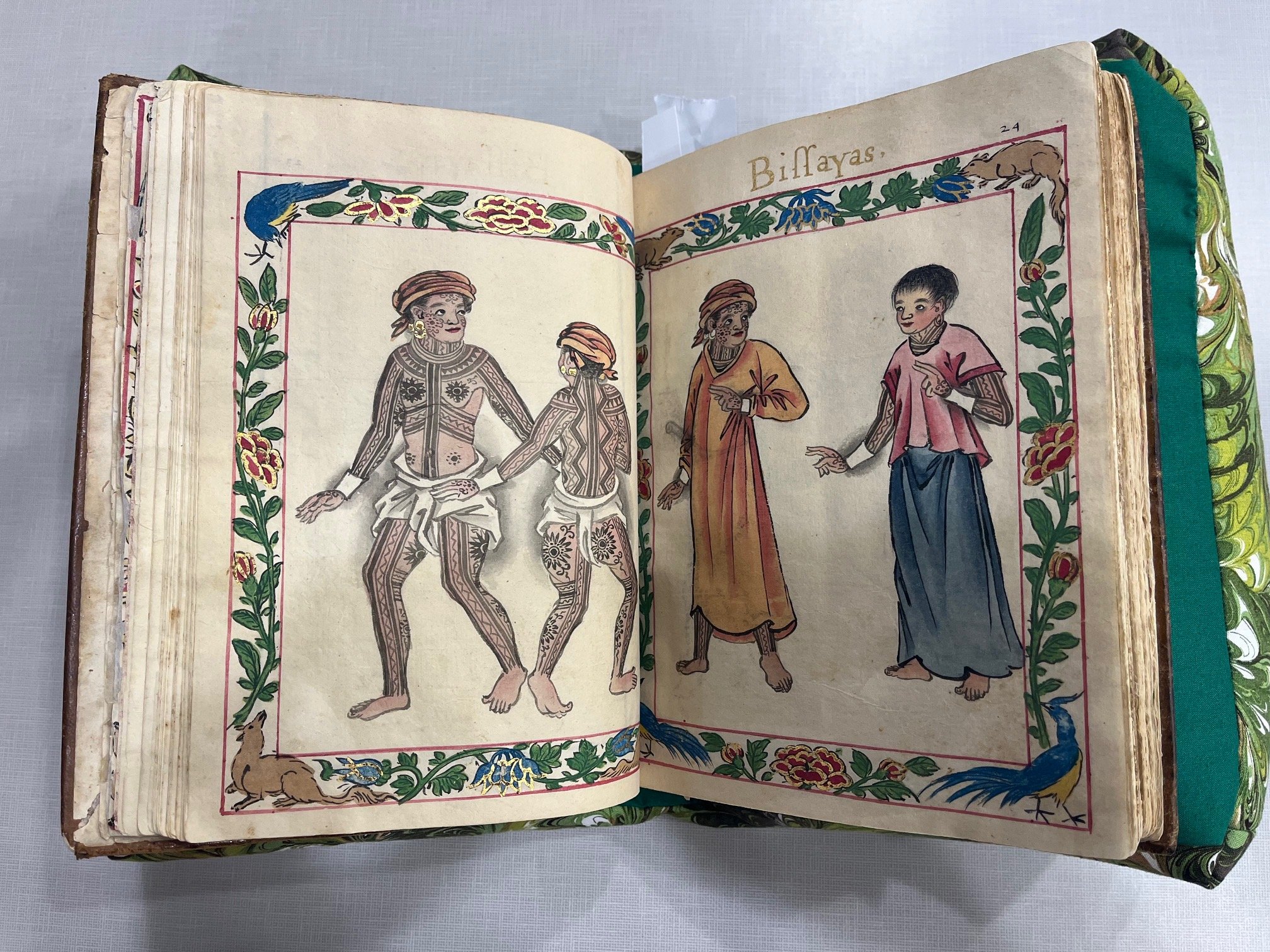

BJ: Growing up, I understood tattoos to be taboo within my community. This was largely due to the assimilative pressures of Christian (particularly Catholic) American culture, associations with criminal activity, and perceptions of the practice as “unsanitary.” I became aware of our ancestral tattoo traditions early on in my personal decolonization efforts. I came across the Boxer Codex pretty quickly, as it is one of the only surviving manuscripts that describes several of the peoples present during the early stages of Spanish colonization of the Philippines. One of the most famous images associated with the book depicts two highly decorated warriors. They are tattooed from their ankles to their foreheads. From there, I learned about Apo Whang Od, one of the last Indigenous practitioners in the Kalinga province, and Tatak Ng Apat Na Alon, a stateside movement dedicated to the perpetuation of our surviving tattoo traditions and the revival of those lost to assimilation. None of the elders in my family were aware that our people held this socially and spiritually important cultural practice for thousands of years.

The Project Begins

AK: After recruiting participants, we met, built trust through sharing our own understandings of our upbringings, and realized the majority of the cohort were creatives. We had artists, musicians, baristas, administrators, etc. within the group. It was great to hear everyone’s story, but we were tied by our ancestry. Some people had really close and positive relationships with their FIlipino identity and just wanted to learn more about our history. Others had more complicated relationships, and our group was a way to reconnect with that side in a safe space. There was crossover lineage, in terms of some of us having family in similar regions, but not familiarity. We had one participant who had already done a lot of research and already had a traditional tattoo.

We had biweekly meetings in person or via zoom. Each meeting we discussed the reading material assigned from our textbook, Filipino Tattoos: Ancient to Modern by Lane Wilcken. We were able to supply the textbooks to all the participants through grant funding from a local arts organization (specifically, a Power Plant Grant from Big Car Collaborative and the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts). We outlined topics to think about when reading the material and presented a powerpoint about those topics that highlighted our own personal research. And in June, we hosted a virtual conversation with Kristine Angeles and Ronna Ventigan, practitioners at Spiritual Journey Tattoo and members of Tatak Ng Apat Na Alon. Using a workshop format for this project helped us to be able to connect with each other while also bringing structure to a project that at times was difficult. Without this format I feel it would have been more difficult to keep things moving.

BJ: We wanted to be transparent that even as artists and arts administrators leading this group, we were also learning this material in real time. We didn’t want to give the impression that we were experts on this subject so much as people creating space and providing resources for all of us to learn about our respective histories and share them with one another. We wanted to connect the cohort with practitioners who engage this work more deeply, and to just be in the presence of people whose experiences aren’t that different from our own. I think what has been unique about this group is that we have individually taken the time to connect our lived experiences with the unfolding of our collective history. This has required a great deal of emotional labor from each of us, and we entered into this process with the understanding that that weight would be shared.

Leaving a Mark

AK: The topics we discussed during our meetings were: Self, Family, Community, Geography, and Spirituality. Each topic was a homework assignment for our participants for reflection, and then we had them present their research to the group. We had multiple people talk about how their research made them grow closer to their family, and discover more about themselves after having the time to sit and reflect on their journey. We also had people unpack traumas, and having the support of the group allowed them to know that they weren’t alone. It was a privilege to hear everyone’s story and what they learned about themselves and their lineage.

I found out the Boxer Codex was here in Indiana after I saw a didactic at Ayala Museum in Manila, PH, and I knew right away I had to see it because it ties into so much of my research. But I can’t explain how happy I am that I didn’t see it by myself. Handling the book that was the origin story to the colonization, persecution, and murder of our people was life changing, and I know I would have felt so alone in that moment if I didn’t go through this experience with this group. A lot of the topics in my personal practice are heavy, and leading this project with the community has made me realize that I’m not alone, and I don’t have to hold all of this by myself.

BJ: It was a powerful experience to actually see and handle the Boxer Codex in person at Indiana University’s Lilly Library and to learn more about the manuscript from the incredibly knowledgeable and enthusiastic Maureen Maryanski. And to conclude the project, the artists in the cohort mounted an exhibition at the Garfield Park Arts Center, and it was humbling to have received so much support from our community opening night.

And I’m excited to share that I commissioned my first batok in April 2024, from Joseph Ash and Elle Festin at Spiritual Journey Tattoo with the support of an Artist Ambassador Travel Grant, awarded by the Central Indiana Community Foundation and funded by the Allen Whitehill Clowes Charitable Foundation. After having participated in the workshop series, those in the cohort who are interested in commissioning their own have already done much of the legwork necessary to kickstart the visual, cultural, and historical research that informs the motifs and patterns they will receive.

Uniting this group over ancestral body art has helped me understand that the markers of Filipino identity were never the full story. Our unwritten history will continue to be remembered, and that the practices we have been studying are connected both to life and what comes after. This work has helped me to contextualize my own creative impulses by drawing upon the narrative, relational, and visual strategies of my ancestors. This work has been a constant source of inspiration as I navigate the material, social, and institutional realities of being a practicing artist.

This workshop series has only begun to scratch the surface of a much deeper history of a practice intimately tied to nature, community, spirituality, and conflict. And I hope that everyone takes from this the understanding that the work of preserving our history through oral and visual storytelling is a shared responsibility with shared benefit.

AK: While this project is coming to a close, it doesn’t feel like the end. This project has built relationships and memories that are now a part of our individual stories.