Water Language: A Conversation with Shanai Matteson and Oscar Tuazon

From the Iron Range in Minnesota’s Northern reaches to industrial farming in the South, to the strength and vibrancy of its Native reservations, it’s impossible to write about rural Minnesota as a singular place. While urban areas concentrate complexity, rural Minnesota exhibits it over expansive distances. Many of the issues that have made the Twin Cities the recent focus of national attention are echoed in the state's rural struggles. These include explosive fights over social and racial justice, capitalist extraction and economic precarity, and a repressive and violent police apparatus. Just as urban uprisings sparked new configurations of social power with mutual aid and solidarity in calls for police abolition and housing reform, rural Minnesota has also been the site of active planning and building of alternative and just futures.

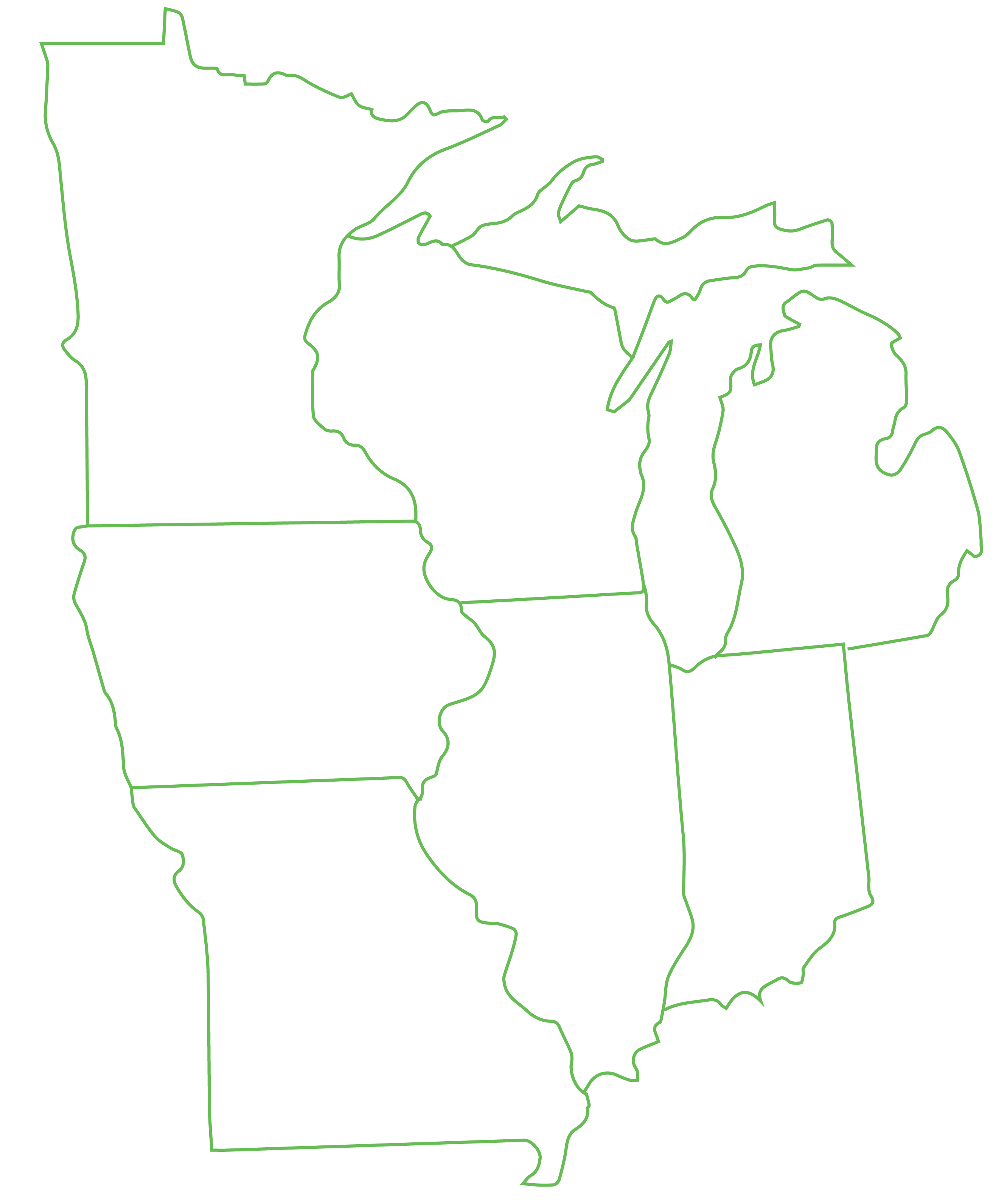

In recognition of the complexity of its rural issues, we focus on a narrower corridor of Minnesota that has become a focal point for arts and cultural work because of its imaginative potential. The headwaters of the Mississippi River begins in Minnesota, and as the river moves Southward, it flows between rural and urban spaces. This iconic river connects the North to the South, and meanders across red and blue counties and states. As a coherent ecological system or bioregion spanning over 2300 miles, the river encourages us to imagine beyond the confines of politically bounded human territories. It inspires solidarity and connection, opening up relational artistic and activist possibilities that span the length of the river. There are a number of examples of this, but perhaps nowhere more powerfully demonstrated than the Stop Line 3 movement, especially during active construction of the oil pipeline (2020-2021). The movement brought together rural Minnesotans, Indigenous leadership, and urban Water Protectors, who collaboratively engaged in fierce environmental, artistic, and cultural resistance to local social and ecological endangerment and global environmental catastrophe. Over 1,000 Water Protectors have been arrested while defending Mississippi River headwaters and its human and non-human inhabitants.

- John Kim

As an aqueous medium for solidarity and connection, the river has inspired networked projects and collaborative initiatives for years. With our contributions to MDW Atlas, we foreground a handful of these.

The following conversation began in Atalka-Atalka, a publication series produced by Cibrián (San Sebastián, Spain) to accompany exhibitions and projects organized by the gallery. The conversation is between curator Thomas Boutoux and Minnesota-based artists Oscar Tuazon and Shanai Matteson about water, language, relationships, the movement-based work of artists and activists to stop oil pipelines, and the importance of honoring Indigenous knowledge and leadership.

Shanai Matteson

Thomas Boutoux (TB): When did the conversation between you two start?

Shanai Matteson (SM): We were aware of each other's work for a few years. We've crossed paths here and there.

Oscar Tuazon (OT): We are among a lot of people who are trying to engage with these issues with the tools that we have. And as artists, this is what we have. I sometimes laugh about it, when I look at the kind of map-making that I’m trying to do currently. I’m trying to understand it, but I’m such an amateur, and my understanding is maybe unsophisticated. But that doesn't stop me. I feel drawn to this, and welcome to engage in it.

SM: When I first learned about Line 3, I would look at maps. I’d go online and try to find my way across the territory using Google Earth views. I was living in Minneapolis and would try to compare those maps to my memory and understanding of this place, having grown up here. I’d use the GIS data that was in the initial Enbridge pipeline proposals to find my way, physically, to the places the pipeline would be laid. So now I have all these memories of construction maps—-maps that we also used during the movement, to monitor construction and prepare for resistance.

OT: You also traced part of the pipeline through a trip?

SM: Yes, I worked with another artist, Sara Pajunen, who is a composer and sound artist. She joined me on this trip. I rode my bike from the end of the pipeline—which is in Superior, Wisconsin, right on the shore of Lake Superior—-and I followed it all the way to the border of Minnesota and North Dakota, stopping at all of the water crossings where the pipeline had not yet crossed the water.

I was visiting each of the sites when they were preparing to drill. It was during the hiatus—-they had to take a break from construction because of mud season. I think it's really telling that the only thing that could really stop them for any significant period of time was mud, which is water and land mixed together. We visited all those sites during mud season, and Sara droned each of them, and put her audio equipment into the river to record sound.

The ride ended up being about 420 miles by bike. (The pipeline in Minnesota is 340 miles.) I did it over about eight days, stopping along the way. I'm really glad I did it that way, because it was my first time experiencing the breadth of the environment the pipeline passes through. The experience is very seasonal, very specific to a point in time. I saw all of the worksites when there were no workers, because of the hiatus. A number of the worksites were under water too, because it was springtime and flooded.

OT: That's really a level of intimacy with that river and the land. One of the things that I have been trying to understand is, like you say, that the landscape is really different seasonally. It's really always a patchwork of water and land. Lakes, rivers, and wetlands are all connected, and I'm tracing these maps, wondering where you draw the line between water and land. It's very time-specific, and an area that might be completely flooded in the spring is then covered in vegetation in the fall. I have been using these USGS geologic survey maps that are available from the government. I find myself absorbed in this question: the boundary and the border. Sometimes I can't see it. But that was my experience on the land too. You might be in an area that's wooded and has trees, walking along, and then you’re in water up to your knees.

SM: Yes! And it changes so much over time, especially here on the upper Mississippi. The river isn't channelized like it is in the Southern part of the United States. So it naturally moves, and more frequently than people realize. Where we live, here in Anishinaabewaki, is riverine forestland. And so, part of the year, the area where we had our camp is actually underwater. Last year was historic flood season, and we had to pick up everything and move it. Then the river went down, and we had a historic drought. Climate change is making these changes more extreme. Part of the conversation around the pipeline is how Enbridge received permits to pump a certain amount of water to make the land dry enough to construct their line. They ended up getting a special water appropriation permit, in the middle of the summer, to increase pumping by 5 billion gallons. They only paid $150 for it.

And when they were creating a route for their new pipeline, they were looking at maps on a computer screen. They were looking for the most direct route in terms of how much it was going to cost them in time and construction. They were not thinking about the water in different seasons or the conditions of that environment over time. They ended up spilling drilling fluid in over 20 frack-outs, and puncturing several aquifers—-the water is under pressure underground, so when you poke a hole in the confining layer of the aquifer, water comes welling up. There are at least three of those aquifer breaches, and some are still flowing. They can't close them. They don't understand, because they were never on the ground. Never connected to place.

TB: Oscar, when was your first time there?

OT: It was in 2018. I went in late spring and then again in the late summer.

SM: At that same time, I was starting to work with Winona [LaDuke] and Honor the Earth. I’d been doing some work around water, using similar artistic frameworks to create a space through art for people to learn and connect, and to have these conversations.

OT: There was a definite sense of urgency. When I first came, I planted a tree as an intention to come back. The second time was with a small group. We spent a few days at the camp, beginning to build a small building intended as a Water School library. It's at the center of this camp that’s active in the training and supporting a community of activists. Winona herself is an incredible library of knowledge, and she conveys that in her own writing. Her way of explaining these issues is so straightforward, comprehensible, and compelling. That was what drew me: just reading her work. So, that was the idea: to make space for that particular kind of knowledge and scholarship, drawing on generations of Anishinaabe knowledge about water, and continuing the work.

SM: It was something Winona was thinking about when she set up the space where I'm living now, next to the pipeline’s eastern Mississippi River crossing. Her vision was a water school and welcome center for activists and water protectors who want to learn, connect with the land, and build relationships. That's what we did here over the course of the last year, and what we're still doing.

TB: One of Enbridge’s policies was creating some kind of divisive environment among the communities.

SM: Yes, I mean—-that's one of the things about capitalism and these extraction projects. The social environment is often vulnerable, and that exposes the people and the place to exploitation. Enbridge put a lot of money into law enforcement here, a place where people are poor and funding for basic services is scarce. They put a lot of money into political organizations that are supportive of their project, and community organizations too—positioning themselves as members of the community here, even though they're a huge corporation based in Canada. So by the time the pipeline construction started, there was already a story built up around who Water Protectors are—-this idea that we were the ones coming from the outside. They would publish the residency locations of anyone that they arrested, especially pulingl over cars with out-of state plates and anti-pipeline stickers. But at the same time, that whole story is also built on a legacy of colonial violence and erasure of Indigenous people who belong here. Who are still here. All of it creates an environment where people will support a corporation putting in a dangerous oil pipeline without any benefit to the long-term health of the community.

TB: I did not understand that it went as far as making up the narratives and stories.

SM: There's some good stuff written by Alleen Brown at The Intercept about what counterinsurgency looks like here. So, you know, at Standing Rock, they had paid operatives like TigerSwan: people who were on the ground posing as activists, infiltrating the movement, working for the pipeline company. In their permits, Enbridge was barred specifically from doing that, so they set up an escrow account to pay for police. They thought they were getting around the permit stipulation barring counterinsurgency tactics, but they just created a different organization to infiltrate public agencies and governing bodies, and then to fund and become local and state law enforcement. Those law enforcement officers live here. They are our government and our neighbors. Aitkin County police know who I am because I live here. Local police—-who are now working for Enbridge—-just called up my neighbors. The sheriff called my family and told stories about me. How he was worried about the people around me. It was deliberately to try to reduce the support for resistance.

OT: The history of infiltration goes back through COINTELPRO and the beginnings of a wider Indigenous-led ecological activism. Within these activist spaces, people are very guarded and cautious, because it really is an issue. There's always this question: who can be trusted? That's the point of this kind of infiltration. To create paranoia and distrust among people who could be working together. I admire the care and vigilance within these environments, and ways that people have to vouch for one another. But it's very challenging, working that way.

SM: Some of the camps and communities had very strict security protocols for these exact reasons. Other spaces were much more open. We were very public-facing, because we had to be. That made things difficult, in some ways.

TB: Do you record oral history in the library too? Or is it mostly existing publications? Zine activity?

OT: It's an ongoing effort, still in a nascent stage. But there is a network of connections through Winona’s work, and part of it is historical. It goes through the early days of the American Indian Movement and the Little Red Schoolhouse, which was started by members of the American Indian Movement in Minneapolis. One of the organizers, Edward Benton Banai, was working in language revitalization and language education for young students. So there is a body of literature through that, and of course Winona is publishing a lot herself. And, then, through the Lodge, oral history is broadcast and used to give a real history and a legal basis to these spaces.

SM: Yes, the Ceremonial Lodge. A historical site and a legal issue. Construction started on the pipeline around the 1st of December of 2020. They started to clearcut toward the Mississippi River, and then they discovered a Midewin Lodge that had been built by Winona and Tania Aubid, who are both Midewin lodge members. And this happened to be in the pathway of the pipeline, so they had to stop construction. They couldn't continue cutting down the trees and get all the way to the river because this lodge is protected under the American Indian Religious Freedom Act, as well as treaties that guarantee the right to hunt, fish, gather, and practice cultural lifeways in ceded territory.

That became a point of dispute, because Aitkin County and the State of Minnesota do not at this time respect those Federal treaty rights and responsibilities, which are the supreme law of the land. So that's where the court cases are now.

White Earth Nation’s Tribal Historic Preservation Officer established what was a Stop Order on construction in that area, based on those treaty laws, and extending from the Lodge 300 feet in every direction. This was something that I thought was really powerful: the inherent rights of Anishinaabe people to pray in that lodge meant that they would need to be able to do that prayer without disturbance. It meant that they shouldn't be able to see construction workers. They shouldn't feel the earth shaking because of the drill, which is less than 300 feet beneath the earth. They shouldn't see drones flying over and surveilling. And so that order was actually a protection around that lodge. That very birthright, and cultural or spiritual practice, became the basis for a treaty stand.

Winona and Tania invited guests into their territory, and put camp around the lodge, and then when Enbridge came to drill, there was a standoff with police. Minnesota’s Department of Natural Resources and Aitkin County law enforcement escorted Enbridge into that prayerful space—-in violation of the treaties and the American Indian Religious Freedom Act, and really in violation of the human rights of Anishinaabe people.

All of that was documented on livestream video, and in legal documents and writings by activists. I am still working to understand what this means for me and for my presence here, and I am working through those questions, again, with the tools I have, which is art.

The 1855 Treaty Authority ended up writing a series of memos to law enforcement, reminding them that they were in violation of these laws and the treaties. Law enforcement said, “Oh, this is just a stall tactic. You built this lodge right here because you meant to stop the pipeline.” And Winona explained to them that Anishinaabe culture is not just in the past. It's not just pot shards in the dirt. These are living people in a living culture. The pipeline wasn't there when she built the lodge, and she built the lodge in order to pray, which is why she was called to that area. To pray. To stop the pipeline. It's her spiritual responsibility to Earth. To Creator. To do these things. To me, this was a really, really powerful cultural action. Why and how do we create in resistance, and what is the potential of those acts of culture and creativity to shape politics, law, and life in our places?

OT: You said it so well, Shanai. And the way it was broadcast—-in real time, through social media—-was really powerful. A pedagogical moment for the whole movement, but also, I think, for the settler communities who live in these areas and don't have a lot of understanding of treaty law, treaty territories, or the real legal underpinnings of the land. It was a generous moment of displaying what the Treaty Authority is, and the spiritual continuance of these practices. The underlying meaning and value of those places. To be able to see that, and follow it through social media, was also a kind of publishing. Knowledge transmission to new generations.

SM: Yes. I feel incredibly grateful to have been able to witness this first hand, and to be part of it. And that Lodge still stands. It's still there. The stand of trees around it was protected. They never did clearcut all the way to the river on this side, and people still visit. Winona and Tania still pray, and they still invite others to come, experience that space, and understand as much as they can about what it means. For me, that was profound too, for my understanding of what it means to be a treaty partner and host for others. Seeing these women stop a construction bulldozer, and actually walk the bulldozer out of the woods into the road. Experiencing it with my body. Supporting the defense of that space. So much of this struggle became about the negotiation of space and language around moving water.

TB: Now the pipeline is finished?

SM: It's done. Yes, the pipeline is done. Oil is flowing through it. They did drill under the lodge, in violation of all of those orders. A group of us were there. We slept there while it was happening. That was a really traumatic experience for a lot of people—-just to be there as it was happening. Many are still fighting in court about ways they took a stand. Attempts to hold Enbridge responsible for the violations that they made during the construction process have been largely ignored.

Today I'm making fabric pieces. Five pieces. They are depictions of the space we’ve talked about here: how it was negotiated, and how it changed. A celebration of life and resistance. I think of them as story maps, as a way of picturing a landscape that makes sense to me, with those different pieces layered or stitched together. I use relief printing to show plant life, and material from the construction site—this high-visibility orange—and some patterns and ribbons that recall, for me, the strong Indigenous women who lead this resistance movement.

Being able to create with my hands is really healing, and the slowness of it also gives me space to think. So much happened that made it impossible for me to take time to create. Being able to spend really deliberate time reflecting on my experience—in the ways that I know how, and the ways that feel good to me. That's what making work is. And that’s what making a life is too. I want to be able to offer that experience to others, specifically other activists and artists who've spent time here or in these movements.

It is just incredible to me that hundreds—really, thousands—-of people came here to stand with the Water Protectors. I want to be able to invite people to come back and to spend some time with the water, to see the land in different seasons, and to make something from that. We have some studio spaces, and we have lodging. Two bunkhouses where people can stay. I think that all extends from Winona’s vision, or where Winona’s vision meets the vision of myself and others who came here to take part in the struggle. We recently purchased a risograph, and we have it here now. And so, thinking about water school and the future of libraries, we will be able to publish things here. I would like artists and activists to be able to come and spend some time, and then be able to make their own publications. Right here.

OT: Yes, and looking beyond the horizon of the pipeline—-what's beyond is actually a really vibrant sense of community and connection to this place. It is just incredibly beautiful. It's an amazing space of nature, and land and water. These connections go beyond the pipeline. These connections are cultural. In a broad sense, that specific community there is a beacon, a powerful example of what rural culture is capable of. You know, a lot of times advanced culture is cast as a strictly urban phenomenon, and my experience in rural Minnesota is that a lot of really engaged activism and adventurous art-making is happening there, and continues to. Continuity is important within the context of socially engaged art practice. For me, it is liberating to know that what I am doing is just one small part of a larger movement. I try not to be burdened with the unrealistic idea that I can produce immediate results, or solve something on my own. Some of my works are windows. Functional prototype windows for Winona’s water school. I try to stay pragmatic, and I embrace a utilitarian idea of sculpture. I try to think how I can be useful.

TB: The alliances between non-Natives, like you two are, and Native people, is something that must be key to continuation.

SM: That needs a lot more conversation. There is an evolving way that non-Indigenous people, specifically settler-descendants, are finding their way to land-based activism, as a means of repairing the land. We have some farm projects, to create more of a regenerative culture. To live in more of a right relationship with this place. But also, we really need to be honest about what brings us here. My relationship to this land is very different from Tania Aubid’s, and in important ways. We both grew up in so-called Aitkin County, but she's here as a survivor of genocide. I'm here as a descendant of people who aided in that genocide, violently displacing her people from specific parts of this land. Of course, this is still Indigenous land, and she and others are still here. But settler-colonial culture dominates the legal system, which is still denying people their rights to practice religious freedoms and lifeways, and to access their lands. All of that has to be in the conversation about what we're doing when we create culture and activist spaces and movements together. That’s really where I am hoping to focus my own activism work and my art, probably for the rest of my life.

This isn't an easy thing. It isn't quick. I'm committed to staying here. I mean, it may not always be right here—-I am here at the invitation of Indigenous women like Winona—-but I want to stay in this area and continue that cultural work, passing it on to my children too.

OT: Right now, the lessons of Indigenous ecology are really essential to maintaining the health of our environment. The deep, generational knowledge of how water moves underground is something that science is only now catching up to. Forest ecosystems. Western science has far to go to just understand some of the basic precepts that Indigenous people have been talking about for a long, long time. So in contrast to thinking about global systems and global economies, we are at a point where it becomes necessary to reinvest in local knowledge. That, to me, is the core understanding: water connects us all, and we belong to the water where we live. It could be an essential part of our education and our sense of belonging in the world to get to know the water we drink. Shanai, your Water Bar demonstrates this in a really profound way. You only serve water, and so people are encouraged to experience a place through tasting it. It is simultaneously essential and so ethereal. We also have to be conscious of how that knowledge gets distributed. Because there's also a kind of extractivism, and extractive practices include knowledge extraction. If ecosystems are going to be actually restored, it can't be at the expense of local knowledge.

SM: A capitalist or colonialist mindset can permeate people and their understandings. Even the culture of activism can become extractive or appropriative. And that's something that is talked about a lot, but not enough. I try to be very conscious of that, and that means always reflecting on what frameworks I'm working or seeing through. It’s really about challenging myself and others around me to stop working in ways that are extractive or exploitative, or erase the contributions and leadership of Indigenous people. I also have to respect the fact that everything is not for me. There's a lot of knowledge and practice that’s kept within Native communities, and that should be honored and respected—those ways of doing things. Protocols. There's a history of violence and theft that underscores why that is so important. But there's always work to do. The word “belonging” is strange—-to be longing. All of us have a really deep connection to land and water, if we can access that longing and work with it. We don't need to appropriate another culture in order to honor it, and find our own connection.

Language is a really important part of that. Just like you said, Oscar, Indigenous ecologies are really vital for the future health of this planet, the people, and the land. And a lot of those lessons are embedded in language, so supporting Indigenous language revitalization in the ways that I can is one part of this, even the ways that we do it in our day to day lives. I've been meaning to take Anishinaabe language classes, and I finally started by joining a language table that everyone is invited to join. I want to figure out how we can incorporate Anishinaabe language into more of the work we're doing here in the land.

OT: I would even say that it's necessary to do this work in the original language. I'm a lifelong Lushootseed language learner. The levels of knowledge are so embedded within the language itself, and it's something you can't just translate word-for-word. There are worldviews embedded within language. The way that any language makes connections within itself is intuitive and can describe a landscape, a cosmology, or a world. We can enter into that way of thinking, speaking, and listening to the natural world, because that way is also literary, and there is sound and music and language that can describe a place too.

TB: We have spoken about the current stakes of the struggle now that the pipeline is fully functional. But there’s even more mining going on—nickel mining for Tesla, for instance.

SM: Well yes. They have not gotten their permit yet, but that's another struggle we are facing now, a new sulfide ore mine, purportedly for Tesla batteries. They're doing exploratory drilling right now. They have drills going 24/7, and they're working on their proposals and maps. It's in the Mississippi River watershed, right next to a number of the best ricing lakes in this region. Sandy Lake, Rice Lakes National Wildlife Refuge, and the East Lake community where Tania is from are all right next to this proposed mine. I'm working with Honor the Earth as a cultural organizer, and the work I'm doing is really about creating the networks and trying to do some cultural work now, so that when we’re at the point where they're receiving their permits, we have information to support legal cases, and hopefully a cohesive movement on the ground that can support Indigenous-led resistance.

The Biden Administration has signaled through executive orders that they will authorize what is called the Defense Production Act. Basically, it allows for money from the Federal government to go toward what they call green energy, which includes new domestic mining and other critical minerals development. They've listed this mine here, in the 1855 treaty territory as one of the projects they might support. I think there are going to be lots of shifts happening politically. It feels very much like the Line 3 struggle all over again, except this time the Biden Administration, the Democrats, and some of the people who would have been allies in the environmental movement see this as a green mine, which is a lot of greenwashing. There are three proposed sulfide mines here in Minnesota. We have not had this type of mining in Minnesota before. It causes acid mine drainage, because the minerals being extracted are contained in sulfur-bearing rock. When you expose that to water and oxygen, it creates acid.

All of these mines are proposed for wetlands. You have a lot of water here, and that’s a recipe for environmental disaster. There has been some strong opposition to mines like this near the protected Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness, a popular recreation site, but this mine is in Aitkin County, a place that has fewer people protecting it.

I've heard people say this gets back to the idea of swamps and mud and muddy places. To a lot of people, it's just a big swamp, and there's not much knowledge about what's actually here. Who's actually here. So the cultural work we're doing is really vital. We’re raising the visibility of the Indigenous communities here, of water and treaty rights, and of what a healthy resistance looks and feels like.

This conversation was slightly edited & condensed from the original.

Thomas Boutoux (born 1975) is a curator, writer, and publisher. He is a founding member of castillo/corrales, a gallery, bookstore, and publishing house operated by a collective of artists, curators, and writers in Paris, established in 2007.

Shanai Matteson (she / her) is a multidisciplinary artist, writer, environmental activist, and cultural organizer. She lives in rural Palisade, Minnesota, where she grew up. Shanai is currently working to help organize cultural and community space at the Water Protector Welcome Center, a pipeline resistance camp and community established by Indigenous women leading the movement to stop the Line 3 oil pipeline. As a non-native woman whose family settled in this region, Shanai sees her cultural organizing work here as a form of service and repair, as well as a way to encourage a just transition to a healthier culture and economy. Shanai works with a variety of rural and urban communities to create collaborative public art projects, documentaries, creative writing and print work, and social or political spaces. Her larger goals are to recognize and deepen her own relationships with people and the places they inhabit together. Through slow and emergent arts activism, Shanai strives to create more caring and reciprocal culture—shifting narratives, challenging hierarchical power structures, and helping her collaborators reimagine and transform the systems they shape.

For more than a decade now, Oscar Tuazon has dedicated most of his work and life to the Water School, both a functional artwork and an experimental school for students of all ages to engage in dialogue and collaborative work with water, first in Los Angeles, then in Nevada, in Minnesota and extending elsewhere.